by Ben Baugh

Experience, longevity and success — Eddie Deas has seen it all.

A career that’s spanned more than seven decades started by bringing butter rolls and coffee to the barn area at Belmont Park. And one of those recipients was none other than Hall of Fame jockey Earl Sande. Eddie Deas has dedicated his life to the Thoroughbred industry.

Born in the United States, Deas would move to Scotland, return to the Bronx, and eventually move to 26 Sterling Road, across the street from Belmont Park.

Belmont Park – Photo Courtesy of NYRA

“I worked through the summers when I was going to school,” said Deas. “I would come out to the barn, started walking horses and getting on the pony. I was rubbing the pony. That’s how I got started.”

Interacting With a Legend

Deas was intrigued with the rider from Groton, South Dakota. Sande had won nine classic races — three Kentucky Derbies, a Preakness and five Belmont Stakes, and piloted the 1930 Triple Crown winner Gallant Fox.

“He rode Man o’ War, and to me that was the biggest thing,” said Deas. “Any time you talk about this business, and you come up with that name, people recognize it.”

Change of Scenery

The late 1940s would find Deas wintering in Aiken, South Carolina. He would return to New York in the spring. However, he would deviate from his routine, and spend the winter of 1949-50 in Hialeah.

“I stayed in New York racing, but at that time we weren’t racing year round, and that’s how I ended up in Aiken during the winter time,” said Deas. “I worked the whole New York circuit. I never went out of that with the exception of going to Aiken. I did go to different tracks as far as going with the horses to race in Maryland and to New England a couple of times, but basically I stayed around New York.”

Deas would spend two winters with Virgil “Buddy” Raines, the first at Delaware Park and the second in Camden, South Carolina. Among the horses Deas would get on for Raines, were Cochise and Greek Song, who were both gifted with talent and ability, and worked effortlessly on the racetrack.

“They had a big round barn,” said Deas. “We had our own house and we lived right on the grounds [in Delaware].”

The Military, a Return to Racing and Continued Success

But duty called and Deas wound up serving in the U.S. Air Force from 1952-56.

“I really missed being around the horses and the racetrack,” said Deas about his time in the service.

However, Deas didn’t miss a beat and he returned to his previous profession — galloping racehorses, many that went on to achieve great success.

The Right Place at the Right Time

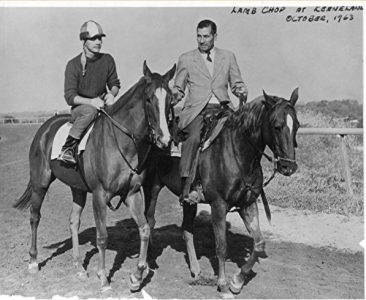

Lamb Chop – Photo Courtesy of Aiken Thoroughbred Racing Hall of Fame and Museum Archives

There was one horse in particular that Deas seemed to be an outstanding fit for in terms of getting his progeny ready for the races. In fact, the horseman galloped a number of horses thrown from this particular stallion’s first breeding season.

“I was on the first crop of Bold Rulers to hit the deck,” said Deas. “Lamb Chop and Jacinto were in that bunch.”

Lamb Chop, bred by Claiborne Farm, campaigned by William Haggin Perry and conditioned by Jim Maloney, was the 3-year-old Champion Filly of 1963. The chestnut filly was inducted into the Aiken Thoroughbred Racing Hall of Fame’s inaugural class in 1977.

Jacinto placed in all eight of his starts. The multiple stakes winner finished with a line of five wins from eight starts, two seconds and a third.

Dreams and Aspirations

Deas loved the thought of possibly being a jockey, but his life was transformed after serving in the United States Air Force. The horseman’s only regret is that he would’ve liked to have pursued a career as a journeyman rider. Still, he would derive great satisfaction from his experience galloping horses for a number of the most prominent outfits on the New York circuit as an exercise rider.

“I love horses and to be on a horse and win a race would be fantastic,” said Deas. “It would’ve been a great feeling. The service caught up with me. I went in, got a little bigger, and there wasn’t a chance when I got out, there wasn’t a way to get back down to my previous weight. When I went in, I weighed around 115-120 pounds. When I came out I was about 135 pounds. It was hard to reduce. That’s what I would’ve tried to different. I would’ve tried to ride races.”

Trusted to Get the Best Out of Racing’s Elite

Prior to entering the service, Deas worked for C.V. Whitney and had the opportunity to get on a number of stakes winners, riding Abe Hisrchberg’s Dinner Gong and Whitney’s First Flight and Mount Marcy. He also rode Whitney’s home-bred Vulcan’s Forge who finished second to Triple Crown winner Citation in the Preakness and second to champion Coaltown in the Gallant Fox. Vulcan’s Forge would also place second, finishing ahead of Ponder in the Narragansett Special, and later would go on to win the Santa Anita Handicap and Suburban. However, there was no shortage of outstanding horses that Deas would go on to gallop during his decades-long career as an exercise rider.

He galloped a filly named Ghost Run, who would work in company with a horse of far greater notoriety, the 1947 3-year-old Champion and Belmont Stakes winner Phlaynx.

“If he was working 3/4s or 7/8ths of a mile, I would join in with another horse at the 3/8th’s pole or the half-mile pole, make him finish, which was a pretty decent thing to do,” said Deas.

Doing It the Right Way

A true horseman, Deas’ patient approach helped horses develop properly, so when it was time to for them to race they performed at or near their best, keeping them at their peak mentally and physically.

“The main thing I always went with when I was breaking horses, especially if it was the first, second or third breeze, I let the horse go off on his own,” said Deas. “I wasn’t one to rush a horse. The first, second and third breeze of a baby, you don’t want to put too much pressure on them because of their bone structure, when they’re growing and forming. It was important not to breeze too fast. You get a nice little breeze into them, but not pushing them, trying to extend them.”

Horseman and Horses Who Made the Game Special

The racetrack allowed Deas to meet many interesting people and his sojourn over the years found him involved with the sport in a number of capacities — as an exercise rider, white cap and, later, on in a supervisor’s role, while working for the New York Racing Association.

Hall of Fame jockey Bill Boland was one of those personalities Deas met during his career.

“He was the first bug rider to win the Kentucky Derby on a horse called Middleground,” said Deas. “I gave him his first drink of whiskey. He was a great rider. He and Allen Jerkens were great friends. He rode Beau Purple for him and did a tremendous job for him.” (Beau Purple beat five-time Horse of the Year three times.)

Gamely, the Champion 3-year-old of 1967, and Champion Older Mare of 1968 and 1969, would eventually be enshrined in the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame and Deas recognized her promise and that of another champion filly, Politely, after riding them.

“I was heads on with both of them, especially when Gamely did it to me. I knew for sure that was a good horse too,” said Deas.

A horse campaigned by Don Pedro Baptista also earned Deas’ admiration. Conditioned by Juan Arias, it was a horse that sold for a meager $1,200 at the Keeneland Yearling Sale — the pride of Venezuela, Canonero II.

“No effort, whatsoever,” said Deas.

Deas also had the opportunity to ride a number of horses for Hall of Fame trainer Laz Barrera, one of them enjoyed a great deal of success in 1973 — the intrepid and courageous chestnut daughter of Windy Sea.

“I got on a filly named Windy’s Daughter, who was a pretty nice horse,” said Deas. “She ran in California and had never won a race over three-fourths of a mile out there,” said Deas. “When he [Barrera] came east, he asked me personally to get on her at Aqueduct.”

The filly seemed to respond to having Deas ride her in the mornings, because she won at distances greater than six furlongs, capturing two jewels of the Triple Tiara.

“She won the Acorn and the Mother Goose, and finished fourth in the Coaching Club American Oaks, because the distance was too far,” said Deas.

Deas had the opportunity to ride a Jerkens charge, an eight-time stakes winner — Top of the Marc Stable’s son of Majestic Prince.

“Sensitive Prince, I worked him for Jerkens for a race in Saratoga, the Jim Dandy, when Affirmed beat him by a nose,” said Deas.

A Place Called Home

The long-time horseman has a predilection for one racetrack in particular, the racetrack where he started his sojourn by bringing coffee and butter rolls to the backside.

“Belmont Park is my favorite because of the distance, the mile and a half,” said Deas. “I thought with the big, wide turns, the horse has a better chance to get himself together, unless you have an absolute speed horse. They can whip around those turns.

“But, to me, that’s a better race. The jocks get hurt with those short turns. You have a lot of room up there. And if you do come over on someone, you can tell they’re playing games.”

Recognizing Talent

Another horse Deas was rather familiar with, was a son of Damascus, the graded stakes-placed Shifty Sheik, who he had an opportunity to get acquainted with when he was working for Robert Debonis.

“He got claimed off us by Steve Jerkens, who was training for Barry Schwartz,” said Deas. “We go to Saratoga, and he [Shifty Sheik] had one bad knee, but he had class — and that’s one thing about the horses he claimed. They would win, if they had a little background. We get to Saratoga and claim this horse off of Oscar Barrera, who claimed Shifty Sheik off of Schwartz. I went up to Oscar in the box, and I said, ‘You better bet on your own horse today.’ He won by a sixteenth of mile. He ended up finishing third in the Woodward Stakes. That’s when they really started investigating [Barrera] after that.”

A Champion in the Making

A Texas-bred by Norcliffe that made a powerful impression on Deas was the sprinter Groovy, who had a number of owners and trainers, but was a source of a cerebral challenge that Deas would often share with others in the racing industry.

“Barry Schwartz said I was the only one who could come up with a trivia question about the only horse that never ran in a maiden race or anything else and that was Groovy,” said Deas. “We beat him in a maiden race in a stake at the Meadowlands, and it was opening day and he was going to run. And I said, ‘You better watch out for this horse here.’”

Groovy was the Eclipse Award-winning Sprint Champion of 1988, a 12-time stakes winner and winner of added money races at ages two, three and four.

“He finished third to Broad Brush in the Wood Memorial,” said Deas. “He got the kiss of death when loading him into the gate. He broke through the gate and they had to reload him too. Most horses never really run as good after. He goes around two turns that day. He just misses and finished third.”

When Deas first became acquainted with Groovy, one thing that he loved about him was his interaction with other horses, how the chestnut colt was an intrepid warrior wanting to touch and engage the other surrounding horses, showing no fear.

Groovy was also playful and would pick up a rubber cone in the shedrow and proceed to walk around with the object. The horse’s equanimity was one of the chestnut colt’s most outstanding attributes.

“He was the best gate horse I was ever on in my life,” said Deas. “He got in that gate, the first time we were breaking the gates open, he’s leaning there and there are two or three horses in there, and they’re jumping all over there, and that doesn’t bother him.

“When the guy says, ‘we’re going to break him with the gates open, we’re going to break now,’ I said, “wait a minute this horse is leaning.’ He said, ‘I can’t wait all day.’ He spun the latch, I almost fell off. That’s how fast he came out of there. That’s how great a gate horse he was.”

Groovy’s connections at the time attempted to sell the horse to Hall of Fame conditioner H. Allen Jerkens before he made his initial start. Prior to his experience in the gate with the impressive-looking chestnut, Deas found himself always having to pick his head up to make him pay attention.

The horseman followed Groovy’s career closely and, though he had not been connected with the eventual sprint champion in some time, Deas would end up giving someone prominent within the New York Racing Association some sage advice.

“I’m up in Saratoga, and the president of the track, Gerard McKeon is walking by me, and I looked over his shoulder, and I said to him, ‘You better bet on that horse,’” said Deas. “They ended up scratching him. It was something to do with the mud.”

Fast forward a week later on Sept. 2 at The Meadowlands and Groovy was entered in the Forever Casting Stakes, his racing debut.

“Barry Schwartz is going over there and running the favorite, I told Barry Schwartz, ‘You better bet on this horse here.’ He paid $16 and beat his horse, who was the favorite. I knew that was a good horse. The morning that I realized this was a good horse, I was just galloping. “

A Lesson Well-Learned

Deas’ brother in-law was Bill Stephens, Woody Stephens’ brother, who provided the horseman with invaluable perspective about gauging a horse’s ability, and one horse in particular, a lightly raced son of Northern Dancer, who would go on to be one of the sport’s great sires — Danzig.

“He was in Aiken as a baby, as a 2-year-old, and he [Bill Stephens] really loved the horse,” said Deas. “I wanted to get inside his head to find out exactly why. I watched him breeze one morning. I saw him come back, he stood there and told me this, and it never left me after that. To look at him, the horse didn’t take a deep breath. He just stood there, walked out of the stall, a horse that galloped once around, then worked 3/8ths of a mile, came back and stood there, and didn’t take a deep breath.

“It just showed how much ability that horse had. It was so easy for him to do. That never left me. And from that time on, if I was around horse that I thought was halfway decent, that’s what I looked for.”

The opportunity to be around high-caliber horses exposed Deas to Thoroughbred racing’s elite and his time in Aiken provided him with a chance to see the depth and quality that would later achieve optimal results at the racetrack.

“When he [Bill Stephens] was there, they had four horses that ran in the Kentucky Derby that came out of Aiken in one year [1974]. Cannonade ran with an entry and the two horses that Frank Martin bought off of them [J.M. Olin’s Cannonade, winner of the 1974 Kentucky Derby, Seth Hancock’s Judger and Sigmund Sommer’s Rube the Great and Accipter].”

Respect, Professionalism and Personalities

It’s Deas ability to recognize quality that has allowed him to succeed in a sport for more than seven decades. His sharp eye and approach to the game is universally respected — from his days as an exercise rider, white cap and, now, as the ever-present sage on the backside of Gulfstream Park, where he can be found diligently clocking workouts along the rail or at the Chief’s Corner. He’s a fixture, whose knowledge and reputation is valued by all of those who have the privilege of getting to interact with him.

One of the advantages Deas had while working in the admissions department as a white cap for the New York Racing Association, was having access to some of the sport’s biggest names and a number of prominent celebrities. He worked for NYRA for 30 years.

“I worked in this elevator and it was almost [like] knew them personally, because you kept on bringing them up and down,” said Deas. “You got to meet everybody. You had a little conversation. I worked in supervision the last 10 or 12 years I was there. I got to meet a lot of people when I was working on that elevator, especially in Aqueduct in that private club.

“I met Ed Sullivan, J. Edgar Hoover, Gen. Omar Bradley and President Eisenhower. The thing that impressed me the most about the meeting with Eisenhower, he came in with a big stockbroker, his name was Allen. He bought a ticket on every horse in the race, and when the race was over, he gave Gen. Eisenhower the winning ticket. I thought that was the coolest thing in the world.”

Thoroughbred racing provided that opportunity to mingle with many of the world’s most recognizable faces. The building was well-designed, said Deas.

“There were four floors, but there were only three floors as far as the grandstand was concerned,” said Deas. “But the Turf and Field was set a little bit above it. The trustees’ room was a little bit above it. It was very private. They had their own dining room, mutuel windows and you were well out of the public’s eye. That’s why a lot of celebrities ended up coming up there. When I got into supervision toward the end of my career, I’d actually go up there and make my rounds.”

Rides of a Lifetime

Deas also had the opportunity to ride Kelso after he retired from racing, when he would be brought out in front of the public at Saratoga.

“I got on Kelso at the end of his career,” said Deas. “They would have a young lady come out in a riding outfit and have her jump him over a few jumps. I got on him in the morning to make it a little easier for her to ride him in the afternoon.”

He would also have the opportunity to get on another prominent gelding, a dual Classic winning New York-bred. It would be a poignant moment for the lifelong horseman.

“I got on Funny Cide for Barclay Tagg,” said Deas. “He was a pony at the time. He was the last horse I was on, in 2007. Then I decided to hang it up. He was my last ride.”

A Couple of His Favorites

The horseman has also had the opportunity to witness 27 Belmont Stakes, with his favorite Belmont being Secretariat’s 31-length victory in 1973.

“When he opened up from the half-mile pole to the quarter pole and was so far in front, I thought he had to stop, thinking that there was no way a horse can open up that far and still go on to win the race,” said Deas. “And he seemed to draw out even further, which made it so impressive.”

Secretariat had already stamped himself among the sport’s elite, prior to cementing his iconic image in capturing the Triple Crown, said Deas.

“We all knew what kind of an animal he was, from his previous races in the Preakness and the Derby,” said Deas. “And he being by Bold Ruler, I had been involved with so many Bold Rulers and knowing how good they were, I wasn’t surprised.”

One horse that captured Deas’ imagination prior to his becoming involved with the sport was Count Fleet, the 1943 Triple Crown champ and a son of the 1928 Kentucky Derby winner Reigh Count.

“I thought Count Fleet was as good as a horse as there was, he won impressively and Johnny Longden rode him,” said Deas. “He was my other big horse.”

An Indelible Imprint

One race that made an indelible impression on Deas, was the 1962 Travers Stakes, featuring two equally talented colts.

“The best race I ever saw was Ridan against Jaipur,” said Deas. “Shoemaker was on Jaipur and Ymanuel Ycaza was on Ridan. They were head-to-head the whole way. Jaipur won by a nose. It was such an impressive display of horsemanship. It would’ve been fair to say that they finished in a dead heat. But Jaipur did win by a nose. It was a great race. That was one of the best races I’ve ever seen.”

A Lifetime of Transformations

Thoroughbred racing has changed markedly and Deas has seen a number of innovations and advancements in medicine that have made the game safer and, in his opinion, improved the sport.

“The medicines that they have today compared to those they had years ago are very different,” said Deas. “You can’t compare the horses because they’re getting so much help compared to what they were getting years ago. Even the care of the racetracks — in those days, they didn’t take much care because they didn’t know much about it.”

However, those changes include the very fibers composing the fabric of the sport and their role in the sport’s final product.

“In those days, people worked harder on their horses,” said Deas. “They would rub them and ice them and stuff like that. They used a brace on a horse after they galloped. You don’t see that anymore. A groom, he earned his money. He had to rub the horse down pretty good.”

Brightening One’s Day

Two of the most colorful personalities Deas ever encountered during his years in racing were one of the sport’s most prominent owners and the other was a strong presence on both the front and backsides.

“Alfred G. Vanderbilt, for as much money as he had, and the great horses that he had, he had a great way of naming horses,” said Deas. “Native Dancer, and the ways he picked out those names was fantastic to see.

“Steve Adika was the jock’s agent for Mike Smith, way back in the day. He was a very funny guy, and he was well-known on the track. He was always spinning people as far as riding was concerned. He had a lot to say, and had a big opinion.”