Sagamore Farm – Photo Courtesy of sagamorefarm.com

When you drive through the spectacular countryside of the Worthington Valley, you can’t miss it. The early style cupolas atop the signature red-roofed barns and miles of white fences dot the Glyndon-Reisterstown, Maryland landscape.

Sagamore Farm is one of the premier breeding and training grounds in the American Thoroughbred industry and one of its most recognizable landmarks. While it is known today for being the 530-acre estate owned by Under Armour CEO and founder Kevin Plank, it will forever be the home of the Grey Ghost of Sagamore — Native Dancer.

Sagamore was founded in 1925 by Issac E. Emerson who invented the headache remedy Bromo-Seltzer. Emerson gave the farm to his daughter Margaret, who bequeathed it to son Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, Jr. in 1933 for his 21st birthday. Vanderbilt would have a significant impact on the sport of horse racing. He pioneered the use of the starting gate and the photo finish camera. And, while still in his 20’s, he would run Maryland’s Pimlico Race Course and New York’s Belmont Park. Surrounded by wealth and opportunity, Alfred personally oversaw the breeding and training of horses at Sagamore.

In 1936, his successful handicap champion Discovery retired to stud at Sagamore and became the farm’s foundation sire. While the horse only sired 25 stakes winners across a 21-year stallion career, he produced three daughters that would help change the sport forever. One daughter produced Bed o’ Roses, a two-time filly/mare champion and member of the Racing Hall of Fame. Another produced Bold Ruler, who was the leading sire in North America a record eight times and sired a horse by the name of Secretariat.

In 1949, Discovery’s daughter Geisha was bred to 1945 Preakness champion Polynesian. On March 27, 1950, the resulting foal was born at Scott Farm near Lexington, Kentucky and was moved soon afterwards to Sagamore. He would call the farm home for the next 17 years, but, along the way, Native Dancer would win 21 of 22 career starts, appear on the cover of Time Magazine and become horse racing’s first television superstar.

Native Dancer won all nine starts during his two-year-old season and won his first of two Horse of the Year titles. Fans across America who watched the grey horse on television were captivated by his thrilling come-from-behind running style. During his three-year-old year, TV Guide ranked him second to Ed Sullivan as the biggest attraction on television.

Native Dancer won all nine starts during his two-year-old season and won his first of two Horse of the Year titles. Fans across America who watched the grey horse on television were captivated by his thrilling come-from-behind running style. During his three-year-old year, TV Guide ranked him second to Ed Sullivan as the biggest attraction on television.

Thousands tuned in as Native Dancer entered the 1953 Kentucky Derby as the unbeaten 7-10 favorite. Anticipation turned to heartbreak when the seemingly unbeatable Grey Ghost was defeated by a head by 24-1 longshot Dark Star. But he would never lose again. In the following weeks and months, he would capture the Preakness, Belmont and Travers Stakes, among others. When he retired during the 1954 season due to a recurring foot injury, he concluded his career with 21 wins in 22 starts and earnings of $785,240.

Native Dancer carried his racing success over to the breeding shed at Sagamore Farm and sired 44 stakes winners, including 1966 Kentucky Derby winner Kauai King. More significantly, he was the grandsire of the great Mr. Prospector and broodmare sire of the legendary Northern Dancer. Visitors to Sagamore today can walk into Native Dancer’s historic stallion barn. During Sagamore’s glory days, every barn and building told a story about the farm’s racing and breeding legacy. There was the famous 90-stall training barn with its quarter-mile interior track. A 20-stall broodmare barn and a 16-stall foaling barn were also in place. And a 7-furlong training track helped prepare some of the greatest racehorses the sport has ever seen.

In 1986, Vanderbilt sold the farm to developer James Ward. Twenty years later, the farm had fallen into disrepair. The familiar red barn roofs had begun to cave in and the one-time bright white fences had started to peel. That is when Kevin Plank stepped in and purchased Sagamore with a long-term plan for a major restoration. With eyes towards the future, yet with deep love and respect for the farm’s past, Plank and team aggressively moved forward and began by restoring the fencing, followed by the historic barns. Then came the outdoor training track. The hallowed 7-furlong ground once galloped on by Native Dancer, Bed o’ Roses, and Discovery was covered with weeds, rocks and broken rails. Plank had it redone and, subsequently, the old footprint of the track was used and a synthetic Tapeta Footings surface was installed.

The ambitions were lofty. It wouldn’t be enough to merely return Sagamore Farm to a major racing and breeding operation. The stated goal then — and now — is to win the Triple Crown. On November 5, 2010, three years after the farm was purchased, dreams began to come true when 4-year-old Sagamore filly Shared Account entered the Breeders’ Cup World Championships at Churchill Downs. Facing a field of 10, including past Breeders’ Cup champions Forever Together and Midday, Shared Account pulled off a 46-1 upset to capture the Filly and Mare Turf championship.

Today, the black, gray and maroon diamond silks of Sagamore compete at racetracks across America. The farm regularly enters winners’ circles with stakes and graded stakes winners and the future is bright with exciting racehorses like Recruiting Ready and Global Campaign.

Just inside the farm’s entry gates is a barn. And in the barn, there is a particular stall. While Native Dancer died in 1967, his stall looks as it did more than 50 years ago — and appears as if he might return at any minute. Just outside the stall is an old white and deep red trunk containing the initials “AGV” on its top. Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt’s legacy is very much alive today. When echoes of yesterday merge with the promise of tomorrow, it is an unbeatable combination.

***

The Hall of Champions

On a beautiful afternoon in the spring of 2006, I walked into the Hall of Champions at the Kentucky Horse Park for the first time. A horse gazed out at me from the first stall on the right. My heart skipped a beat, as the nameplate on the door said Cigar. To my immediate left, the stall’s door opening was filled with a horse’s large backside. I would later learn this was the most pleasant greeting I could expect from the great John Henry.

Up and down the corridor were stalls occupied by notable champions from the racetrack and the show ring. Both then and now, it is one of the closest places to horse heaven you’re likely to find here on earth.

The Kentucky Horse Park opened in 1978 and is Kentucky’s largest state-owned tourist attraction. Set on more than 1,200 acres in Lexington, Kentucky, the park is a premier international equine theme park dedicated to celebrating man’s relationship with the horse through education, exhibition, engagement and competition.

In 1979, a horse van arrived at the park carrying eight-time Eclipse Award champion and three-time Horse of the Year Forego. The Hall of Champions was born. For the next 18 years until his death at age 27, the immortal racehorse would greet and entertain millions of fans and visitors. During the following decade, the Hall of Champions added legends from multiple breeds including champion Quarter Horse Sgt. Pepper Feature, the great five-gaited American Saddlebred CH Imperator, and the incredible harness racing star known as “The Horse that God Loved” — Rambling Willie.

If Forego helped put the Kentucky Horse Park on the map, John Henry elevated it to the next level. When the irascible, yet beloved, gelding joined the Hall of Champions in 1986, the attention he brought to the Kentucky Horse Park contributed to what is today an annual draw of nearly 800,000 visitors. Most fans that traveled from all parts of the country and world to visit him, walked away with a unique, lasting memory. There were the 200 or so fans that showed up for both his 30th and 32nd birthday celebrations. John’s one-time jockey Chris McCarron was a regular visitor and was there to say goodbye to his friend during his final hours.

In 1999, a new resident joined the Hall of Champions. He was unconquerable, invincible and unbeatable. He was Cigar. While John Henry was ranked by the Blood-Horse as the 23rd top Thoroughbred racehorse of the 20th Century, Cigar ranked 18th. They were the highest ranked living racehorses in the world and lived directly across the aisle from one another. As a matter of fact, the duo would race each other up and down their parallel paddocks and you would have been hard-pressed to find a greater match race in the sport’s history.

During the Hall of Champions’ 40 years, approximately 22 legends have lived in this incredible barn. These include Thoroughbred Hall of Famers Point Given and Alysheba, Kentucky Derby winners Bold Forbes, Funny Cide and Go For Gin, and Breeders’ Cup victors Kona Gold and Da Hoss. Nobody has lived in the Hall longer than 1993’s Harness Racing Horse of the Year Staying Together (24 years and counting), and Quarter Horse champion Be A Bono and Standardbred great Mr. Muscleman have been in love with one another since they joined the Hall in 2009.

While countless Kentucky Horse Park visitors have fond memories of the equine heroes they’ve met over the years, special relationships have also been formed with the dedicated Hall of Champions staff and volunteers as well. There is 92-year-old Gene Carter who may be the last person alive to sit on the back of the great Man o’ War as a youth. When Gene’s wife died in 2003, he wanted to get out of the house and subsequently began working full-time at the Hall. Most special in the hearts of so many is the late Cathy Roby. The longtime Hall of Champions manager worked at the Hall for 20 years until her death in 2011 at age 62. Roby was probably best known as John Henry’s closest companion at the Horse Park and cared for him during his final 16 years. Others who have left their mark on the Hall include Wes Lanter, Tammy Siters, Robin Bush, Barbara Ratteree and so many others.

Today, the Hall of Champions is home to eight retired Thoroughbred, Quarter Horse and Standardbred racing legends. The horses are paraded in presentations twice a day from April through November. The performances can be quite moving, with video clips highlighting the particular champion’s racing career before each is escorted individually into the circular pavilion to the applause of visitors. While there are no formal presentations in December through March, visitors can still stop by the stalls and adjoining paddocks and interact with these ambassadors for the breed and the sport.

As visitors enter the long, paddock-lined walkway that leads to the entrance of the Hall of Champions, they are met by an honor guard of three sculptured bronze statues atop graves showcasing the final resting spots for John Henry, Alysheba and Cigar. On the opposite side of the Hall’s barn and beyond the show pavilion is the Memorial Walk of Champions. A serene, tree-lined path lets you stroll by more than ten graves of past equine residents of the Hall, including the mighty Forego.

Each tombstone contains an affectionate phrase about the horse and what they meant to fans and the Kentucky Horse Park alike. The one anomaly along this path is the grave of Invisible Ink. The 2001 Kentucky Derby runner-up never lived at the Horse Park, yet was loved by so many racing fans across America for his courage. So he was given a final resting place here among the greats. The phrase on Inky’s tombstone says, “The Heart of a Champion Beats Forever.”

It is a testament that could be said of every one of the residents of this incredible place… past and present.

***

Greyhound’s Stall

He was The Grey Ghost. The Horse of the Century.

Across his racing career, he established no fewer than 14 world records. At age seven, he effectively partnered with a female to set two of those records. He was an incredible combination of beauty and power. And after he retired to a small Illinois farm, visitors from all 50 states and more than 30 countries around the world came to see the gelding over the next 25 years.

In the rich history of harness racing, there has never been a trotter quite like Greyhound. He was born in March of 1932 at Kentucky’s legendary Almahurst Farm, which also produced the great Kentucky Derby champion Exterminator. Today, the estate is Ramsey Farm, property of successful Thoroughbred owner Ken Ramsey and his family. As a yearling, Greyhound was consigned for sale at the Indianapolis Speed Sale in the fall of 1933. Even though America was in the thick of the Great Depression, Greyhound was sold to Colonel Edward John Baker for a respectable $900 (about $17,000 in today’s dollars).

E.J. Baker was a native of St. Charles, Illinois and created Red Gate Farm just north of the city. The farm would ultimately become known for its talented trotters including Winnipeg, Labrador and Sister Mary. Greyhound showed promise during his two-year-old season, winning four significant juvenile races. His three-year-old season was highlighted by his victory in the sport’s most prestigious race, the Hambletonian Stakes in Goshen, New York. He dominated harness racing in 1935, winning 18 of his 20 starts. He was unbeaten in every race, with his only two losses coming in heats.

For the remainder of his racing career, Greyhound would only lose one more race — as a four-year-old. The world records he broke were often his own; and many endured for more than three decades. In 1939, at age seven, he didn’t start in a race because there was no horse prepared to race against him. Subsequently, he ran in exhibitions against the clock.

If Greyhound was the king of the trotters, the queen was Rosalind. The six-year-old mare won the Hambletonian in 1936, the year after Greyhound captured the title. In the summer of 1939, the two champions came to Syracuse, New York and were harnessed in tandem together and lowered the team-to-pole world record to 1:59. One week later, at the Indiana State Fair, they lowered their own record to 1:581/4. It was the closest thing to a love affair that horse racing has ever seen.

Greyhound’s racing career came to an end at the close of the 1940 season. Across a six-year career he won 71 of 82 heats and 33 of 37 races, with three of his four defeats coming as a two-year-old. He retired to the Chicago area where he split time between Colonel Baker’s Red Gate Farm and Baker’s Acres in Northbrook. As he grew older, he turned nearly white and would tour racetracks across America adorned in his red blanket. In 1949, Greyhound moved to Flanery Farm in Maple Park, Illinois. Baker loved the horse so much he built an elegant 12’ x 21’ tongue-and-groove, oak-lined stall, supplemented with air-conditioning, recessed lighting and a wide picture window overlooking an adjacent sitting room so Greyhound could lean through the opening and greet fans.

It was at these modest stables where Greyhound welcomed thousands of visitors from around the world. One young man said he came to America to see “the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon and Greyhound.”

For nearly 25 years, the horse was loved and cared for by Dooley and Leona Putnam and his trainer Doc Flanery until the great champion passed away on Feb. 4, 1965 at age 33.

Long after Greyhound’s death, Flanery Farm remained in family ownership and the facilities were leased to other Standardbred breeders. As time marched on, the legendary stall was kept intact — until 2013, when word spread that the farm, which had become run down, would be leveled. Two women from the area, Jan Heine and Nancy Brejc, had formed a lifelong friendship and had worked at Flanery Farm in prior years caring for horses of various lessees. Both in their mid-fifties by 2013, Heine and Brejc had developed an obsession with Greyhound over the years and kept tabs on his stall. Before the farm was razed, the women came to Flanery in the cold of November and spent a total of 193 hours over 11 days disassembling both the stall and sitting room, nail by nail and board by board. This included a few solid oak boards containing Greyhound’s tooth marks. The painstaking process included numbering each board as if it were a piece in a puzzle so it could be put back together exactly as it once had been.

Every part was stripped down and packed safely away for the winter. In May of 2014, it was time for Nancy Brejc and Jan Heine to hit the road with Greyhound’s stall in tow. An 840-mile road trip was made to Goshen, New York and the Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame. After a few years of planning and reconstruction, Greyhound’s rebuilt stall was opened to the public on July 2, 2017.

I visited the museum on a trip to New York. When I walked into the sitting room and then into the stall, I immediately felt a deep reverence for one of the most amazing racehorses that ever walked the earth. Beautiful haunting music played on a background video as the voice of his late caretaker Dooley Putnam reminisced about his longtime friend from a 1965 interview. Artwork and photos lined the oak walls and Greyhound’s racing tack and various trophies and treasured mementos were also displayed.

Magical? Unquestionably. As Stanley Harrison once wrote…

Somewhere in time’s own space

There must be some sweet pastured place.Where creeks sing on and tall trees grow

Some paradise where horses go.For by the love that guides my pen

I know great horses live again.

***

Fair Grounds Race Course

There is no city in America like New Orleans and there is no racetrack like the Fair Grounds. Located two miles from the French Quarter in the heart of the Crescent City, these beloved grounds have been a staple of southern Thoroughbred racing since 1872. Much like the spirit and resilience of the city and its people, the story of the Fair Grounds has been one of survival. Across 150 years, the track has overcome the Civil War, two fires, bankruptcy and Hurricane Katrina. Yet, today, it prospers.

Technically speaking, the Fair Grounds is the second oldest horse racing track still in existence in America (after New Jersey’s Freehold Raceway, which opened its gates in the 1830s). Horse racing has taken place on this New Orleans’ real estate since 1852, when the facility was known as the Union Race Course. It closed five years later and re-opened in 1859 as the Creole Race Course. The name was changed to the Fair Grounds in 1863 and the first official race card and call to post occurred on April 13, 1872.

The track has seen its share of historic and colorful characters over the years. During that first meet in 1872, General George Armstrong Custer was an owner with horses stabled on the grounds, four years before he and his men were killed at the Little Bighorn. Four years after the conclusion of his presidency, Ulysses S. Grant attended the track’s 1880 spring meet. There were big personalities on the racecourse as well. Winnie O’Connor, one of the sport’s first great jockeys, spent a good portion of his career at the Fair Grounds and was once suspended for discharging a pistol in the jock’s quarters.

Many great horses have run at the track as well; however, three of them captured hearts of Fair Grounds’ racing fans unlike any other and are remembered to this day.

There has never been a mare like Pan Zareta. From 1912 through 1917, she ran 151 times on 24 different tracks across America, winning 76 times. In fact, she finished in the money in 85 percent of her starts regardless of the high weights she often carried. She once toted 146 pounds in a victory, conceding 46 pounds to the runner-up. Pan Zareta was in training during her 8-year-old season when she died suddenly of pneumonia in her stall at the Fair Grounds. She was buried in the track’s infield.

Six years after Pan Zareta’s passing, a young black colt put the Fair Grounds on the map once again when he won the 50th running of the Kentucky Derby. His name was Black Gold. In one of the most thrilling renditions of the Run for the Roses, Black Gold was bumped during the race’s final 70 yards and driven five wide but recovered to win at the wire.

At age seven, tragedy struck during the Salome Purse at the Fair Grounds when the colt broke down in the stretch, finishing the race on three legs. He was euthanized at the track and heartbreak once again fell across New Orleans and the Fair Grounds. Black Gold was buried on the track’s infield near the sixteenth pole and close to his fellow Hall of Famer Pan Zareta. Each year, the Black Gold Stakes and the Pan Zareta Handicap are run at the race course and the winning jockeys place a wreath on the respective graves of the two legends.

From 1977-1990, the Fair Grounds was owned by Thoroughbred owner and trainer Louie J. Roussel III. In 1988, a three-year-old colt owned by Roussel and popular New Orleans car dealer Ronnie Lamarque captured the Fair Grounds’ signature race, the Louisiana Derby. After a disappointing third place finish in the Kentucky Derby, Risen Star went on to capture the Preakness Stakes and then won the Belmont Stakes by a dominating 14 ½ lengths. An injury that occurred in the Belmont resulted in his immediate retirement but he was awarded Champion 3-Year-Old Male honors at the close of the year. The Fair Grounds was home to five of Risen Star’s eleven career starts and he is remembered each year with the Risen Star Stakes for three-year-olds.

When visitors arrive at the Fair Grounds today, they encounter twin gatehouses built in 1862 that still stand at the track’s front entrance on Gentilly Boulevard. These remnants of yesteryear have survived the erosion of time that other track landmarks have not. At least six different grandstands have been erected over the years. A fire at the track three days after Christmas in 1918 destroyed the grandstand; and another fire in 1993 destroyed both the grandstand and clubhouse.

Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005 and the property was inundated with water and a section of the grandstand roof was torn off by the storm’s powerful winds. Once again, the Fair Grounds persevered and, after closing for a year, it was reopened in late 2006.

The facility today is a celebration of glass. The grandstand structure is two stories tall, comprised mostly of windows and, as a result, each racing patron can see every point of the racecourse from their seat.

Food at the Fair Grounds? Hey, you’re in New Orleans and the menus provide the cultural experience you would expect, including jambalaya, seafood gumbo, oysters, po’ boys and many other Creole delights. The Fair Grounds is also home to one of the world’s largest and most popular concert events — Jazz Fest. This annual celebration of the music and culture of New Orleans and Louisiana takes place over seven days in late April and early May. Spread across 12 different stages, the event drew a record 650,000 attendees in 2001.

In the world of horse racing, there are few places as distinctively special as the Fair Grounds on Thanksgiving Day. While the annual racing meet begins in mid-November and runs through late March of the following year, for so many years the race course’s opening day was on the holiday. These days, Thanksgiving at the track has the feel of Mardi Gras in November. It is an equine costume party complete with Bloody Marys in a carnival-like atmosphere. Most importantly, the patrons that day skew heavily young and turn out in droves. They come to celebrate life and New Orleans and provide great optimism that this beloved track may be around for a third incredible century.

***

Calumet Farm

I walked toward the stall and saw six nameplates on the door. The top plate said Alydar. I moved on to the next stall… Whirlaway. And the stall across the way… Citation. For lovers of American Thoroughbred horse racing history, there are few places that evoke the emotions one feels standing in the famous stallion barn at Calumet Farm.

Drive along both Versailles and Van Meter roads in Lexington, Kentucky and you can’t miss it. The white, four-board fences, barns and outbuildings that are trimmed with rich green and red, and the distinctive red gate at the farm’s entrance. The numbers produced at these 762 acres are staggering — a record eight Kentucky Derby winners, two Triple Crown-winning colts and three Filly Triple Crown winners. The farm has produced 11 horses that were inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame and six horses that were named Horse of the Year in the 1940s.

It all began more than 100 years ago and 400 miles away from Lexington in Libertyville, Illinois. William Monroe Wright was the founding owner of the Calumet Baking Powder Company and loved Standardbred trotting horses. Ten years later, in 1924, Wright relocated Calumet to Kentucky to take advantage of the more favorable climates for his horses. When Wright died in 1932, his son Warren Wright Sr. took over the business and set about converting Calumet into a Thoroughbred breeding and training operation. After Wright purchased interest in the successful European sire Blenheim II, he purchased a young colt in 1936 named Bull Lea, who became the farm’s foundation sire and Calumet would soon become one of the most successful operations in Thoroughbred racing history.

For five decades, Calumet garnered more than 2,400 wins with total earnings of over $26 million. The farm was the number one money-earner in horse racing for twelve years. Its dominance of racing in the 1940s was unlike any stable before or since. Led by trainer Ben A. Jones and his son Jimmy, the Calumet reign would begin in 1941, when Whirlaway captured the Triple Crown. Soon to follow were championship seasons from Twilight Tear, Armed, Coaltown, Pensive and Ponder. In 1948, the great Citation became Calumet’s second Triple Crown winner in seven years and, three years later, “Big Cy” became the first Thoroughbred racehorse to win $1 million.

When Warren Wright died in 1950, his widow Lucille Parker Wright inherited Calumet and ran it successfully for more than 30 years. While the dominance of the 1940s had passed, the devil’s red and blue silks were continually showcased in winner’s circles across the decades and included Kentucky Derby wins in 1952, ’57, ’58 and ’68. Calumet rose to prominence again in the late 1970s behind trainer John Veitch and champions Our Mims, Davona Dale, and Before the Dawn. In 1978, a Calumet three-year-old superstar reminded racing fans of the farm’s glory days.

His name was Alydar.

As part of one of the greatest rivalries in the sport’s history, Alydar finished a close second to Affirmed in all three thrilling renditions of 1978’s Triple Crown races. He retired to stud the following year and became a major success for Calumet, siring such champions as Easy Goer, Alysheba, Strike the Gold and so many others.

Despite his success, Alydar could not prevent the farm from entering a period of serious decline in the 1980s. When Lucille Wright Markey died in 1982, the farm passed to the heirs of Warren Wright. In 1990, Alydar was America’s leading sire, but after his mysterious death on Nov. 15 of the same year, a cloud of suspicion was cast over the business and accelerated Calumet’s continued collapse. Not long afterwards, the farm went bankrupt, dispersed its horses, and sold the original devil’s red and blue silks to a Brazilian investment group. In 1992, Calumet was put on the auction block.

And then everything changed overnight, and Calumet rose from the ashes.

Successful businessman Henryk de Kwiatkowski from Canada always admired the beauty of Calumet during his trips to Lexington. When he learned the farm was up for auction, he seized the opportunity and won ownership with a closing bid of $17 million. During the following ten years, Kwiatkowski and team restored Calumet to its former beauty. In 2012, The Calumet Investment Group purchased the farm for $35.9 million and leased the farm to American businessman Brad M. Kelley. The following year, Calumet won its eighth Preakness Stakes title when Oxbow captured the 138th running of the classic race wearing the farm’s new black silks with gold chevrons.

We will likely never see again the dominance achieved by Calumet in the 1940s; however, the farm has returned to eminence on the Thoroughbred racing stage. Kelley has continued to invest both dollars and horses into the operation and this is evident today via a strong collection of twelve stallions. Stalls once occupied by the likes of Citation, Bull Lea and Tim Tam are now home to Oxbow, champion English Channel and Keen Ice.

Calumet has never forgotten its past. The farm’s philosophy is to model the past and raise a good horse. And not just a good sales horse, but a good, sturdy two-turn Derby horse.

A visit to Calumet today is an echo of yesteryear. Thirty-five miles of iconic white fences surround the lush landscape. The farm’s training track, stables and barns have changed very little across 75 years. If walls could talk, it would be fun to enter the two-and-one-half-story, brick Main House on the southwest corner of the property.

And if the historic stallion barn is hallowed ground, Calumet’s equine cemetery is truly magical. Nearly 65 headstones provide a journey through racing history — so many champions who contributed to an incredible legacy of success. Perhaps the late, great sportswriter Red Smith described it best: “Calumet laid it over the competition like ice cream over spinach.”

***

The 6666 Ranch

When I stepped foot onto the 6666 Ranch, I gazed up at a big, blue, beautiful Texas sky and couldn’t imagine it any other way — legendary Quarter Horses, a family legacy, superior Black Angus Cattle and oil. These are the hallmarks of this iconic landmark. Also known as the Four Sixes, the ranch may well be the most important place in the history of American Quarter Horse racing.

The ranch’s main headquarters is in Guthrie, Texas. This isolated town of 160 residents has one store, one gas pump, and is 30 miles to the next closest gas station and an hour and a half to the next town. More than 48 windmills dot the Four Sixes’ 275,000-acre landscape, which includes another location near Panhandle, Texas. This enterprise collectively known as the Burnett Ranches once encompass more than a third of a million acres.

The origin of how the Sixes got its name has led to some colorful stories across the years. The most popular tale is that 6666 founder Samuel “Burk” Burnett won the original ranch in a poker game, with a winning hand of four sixes. It’s a fun and engaging story — but it never happened. The truth is Burnett purchased 100 head of cattle wearing the “6666” brand in 1868 and, with the title to the cattle, came ownership of the brand. Today, the Four Sixes remains one of the most prominent commercial cattle ranches in Texas and maintains a breeding herd of some 7,000 mother cows who continue to display the 6666 brand.

As the American West developed, with increased population during the late 1800s, open ranges began to disappear, as cattle owners were required to fence off their individual lands. Burk Burnett set about acquiring his own land holdings and purchased the ranch in Guthrie that is the nucleus of what is the 6666 Ranch today. It was the discovery of oil on Burnett land that allowed the business to grow. The first discovery occurred in 1921 at the location north of Panhandle, and the resulting well produced constantly for more than 50 years. Another large field was struck in 1969 at the 6666 Ranch in Guthrie — and that field is still being developed.

Outside of oil, the most important change was the addition of a formal equine breeding program at the Sixes in the 1960s. The ranch established a legacy for breeding world-class American Quarter Horses back in the 1940s, with influential stallions Hollywood Gold and Grey Badger II; and Cee Bars added to that tradition throughout the 1950s.

Fans of horse racing will always debate over who is the greatest horse the sport has ever seen. When it comes to American Quarter Horse racing, however, conversations often begin with one name — Dash For Cash. During his 23 years on earth he illuminated the skies of the industry both on the racetrack and in the breeding shed. On the track, he was a two-time world champion, winning 21 of his 25 career starts and amassing $507,687 in earnings. He retired from racing at the close of the 1977 season and spent the remainder of his life at stud at the Four Sixes. As a stallion, he sired 751 winners, with 135 stakes winners and 16 world champions. In May of 1996, Dash For Cash was euthanized due to complications of equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM).

The succession of champions associated with the Sixes that followed includes some of the greatest names the sport has known. Mr Jess Perry became a living legend as one of only three Quarter Horses to sire racing earners of more than $52 million. His son One Famous Eagle won more than $1 million on the track and is the all-time leading first crop sire in history. Other greats have included Special Effort, Streakin Six and Eyesa Special. Today, the ranch stands 15 to 20 of the top racing, performance and ranch Quarter Horse stallions found anywhere in the world. Each year, between 1,000-1,250 mares are bred at a state-of-the-art facility and the Sixes maintains its own elite broodmare band of nearly 160.

Throughout their long and colorful history, the Burnett Ranches have been a story of family. When Burk Burnett died in 1922, the legacy continued with son Tom, who continued the growth and reputation of the enterprise. The third generation assumed the mantle in 1938 with Anne Valliant Burnett. “Miss Anne” took special interest in the ranch’s Quarter Horse breeding operation and assisted in the creation of the American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA) and the sport’s Hall of Fame. Prior to his death in 1922, Burk Burnett willed the majority of his estate to Miss Anne in a trusteeship for her yet unborn child. When Anne died in 1980, her only child and daughter, Anne Burnett Windfohr Marion took over control of the Sixes and inherited her great grandfather’s ranch holdings by direction of his will. “Little Anne” grew up on the ranch and learned to ride horses and earned the respect of the ranch’s cowboys. As with prior generations, she has a deep commitment to the continuing success of the ranch.

Wide Open Spaces

If you look around the 6666 Ranch and have a sense of déjà vu, it may be because the land was seen in advertisements for Marlboro cigarettes in the 1960s and 70s. The cowboys here are straight out of central casting and many ranch employees are among the second or third generation from their family to work at the Sixes.

Visitors to the ranch can stop by the famous 6666 Supply House on the way into town. Guthrie’s only store was built in 1900 by Burk Burnett and is still a place where both employees and locals can purchase items such as groceries, clothing, hardware and tires. At the ranch, one of the highlights is the 11-bedroom ranch home built by Burnett for $100,000 in 1917, an incredible sum of money at that time. It was here where Burnett hosted Theodore Roosevelt, Will Rogers and other friends.

Perhaps what is most magical about the 6666 Ranch is a red 16’x16’ stall on the grounds. For so many years, it was home to Dash For Cash and, today, champion One Famous Eagle will peer out at you from the same stall. It is sacred ground in the world of American Quarter Horse Racing and symbolic of the tradition of excellence the Four Sixes has consistently showcased for 100 years. When you close your eyes and imagine a classic Texas ranch, the Four Sixes is what you see.

***

The Home of Kelso

“Once upon a time there was a horse named Kelso…but only once.”

— Joe Hirsch

With the utmost respect to Secretariat, Man o’ War and Citation, he may have been the greatest of them all. He won an unprecedented five consecutive Horse of the Year awards. He set nine track records, was victorious on twelve different tracks, won on dirt, grass and mud — in winter, summer, spring and fall. He carried 130 pounds or more on his back 24 times, yet still won 13 of those races, placing in five and finishing third once. Kelso was the all-time money winner when he retired and it was a record which lasted for fourteen years.

Enter the front gates of Woodstock Farm in Chesapeake City, Maryland and walk along a beautiful road, lined with tall sycamores and pines, and you will feel their spirit wherever you go. They are Kelso and his beloved owner, Allaire du Pont. Foaled at Claiborne Farm in Kentucky in 1957, Woodstock was Kelso’s home for most of his 26 years. This former cattle farm and its 300 acres was purchased by du Pont and her husband Richard in 1941. They eventually expanded the property to 800 acres and moved their horses and Bohemia Stables operation from Middletown, Delaware to this historic town on the banks of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. It was an idyllic second home and retreat for Allaire and Richard to spend time with their two young children and enjoy a shared passion for horses and planes. Tragedy struck, however, in 1943 when Richard and three other men were killed when a glider they were flying malfunctioned.

Kelso and his dam, Maid of Flight, left Claiborne and came to Woodstock. He was a scrawny colt with an attitude. Allaire du Pont gelded him with hopes of calming him down, but it didn’t seem to help. He continually dumped his riders and was a cribber to boot. She tried selling the son of Your Host in 1959, during his two-year-old season, but nobody was interested. A diamond lay hidden in the rough however. “Kelly’s” inner competitive fire reaped benefits as a three-year-old in 1960, when he won eight of nine starts and captured the first of what would be multiple Horse of the Year and divisional honors.

There was no looking back. With each passing season, Kelso’s trophy case grew and so did the size of the crowds at his races and his incredible popularity among American sports fans. Offseason periods of rest and relaxation were spent at Woodstock. He lived in a very large stall, with his name on the welcome mat, and slept on a bed of sugar cane fibers. He drank only bottled Mountain Valley spring water from Arkansas due to recurring bouts with colic. And his diet? In addition to the normal hay and roughage, the mud-colored gelding had a sweet tooth that resulted in ice cream sundaes and his fans would send lumps of sugar individually wrapped in paper bearing his name and photograph.

Kelso had his own private mailbox at Woodstock to accommodate an incredible volume of fan mail. At the peak, he received up to 500 letters a week from fans of all ages — and each letter received a response. Through the years, he shared his paddock and stall with a number of beloved canine and equine friends. His personal bodyguard was a small dog named Charlie Potatoes who slept with Kelso at night and rarely left his sight. He also grew close to stable ponies and longtime friends Spray and Pete.

After an injury in the spring of 1966, nine-year-old Kelso was retired from the sport and returned to Woodstock for good. Allaire du Pont would ride Kelso across the grounds of the farm, galloping through the surrounding woods, streams and trails. One year after his retirement, Kelso learned to become a show jumper and, in subsequent years, would perform at racetracks across the country and at Madison Square Garden. At home in Maryland, he participated with du Pont in fox hunts and the competitor glint was still present in his eye as he watched Woodstock horses breeze on the training track from the far end of his paddock.

In 1974, a 17-year-old Kelso was slowed by arthritis and only occasionally accompanied Mrs. du Pont on her journeys around the farm. In the early ‘80s, he was well into his twenties and visitors still came to see him. On Oct. 16, 1983, Kelso died at the age of 26. A heartbroken Allaire du Pont buried him in an equine cemetery behind the farm office within a circle of Greek columns and tall trees. Woodstock had been du Pont’s primary home since 1960 and she continued to live at the farm until her death at age 92 in 2006.

Woodstock Farm still thrives today, with half of the farm dedicated to farming and the other half to the breeding of thoroughbred horses. Visitors are welcome and can visit the farm office, a former late-1800’s post office which serves as a small museum, paying tribute to the life of Mrs. du Pont. An entire room is dedicated to a life of racing success with walls and shelves adorned with photographs, paintings, plaques, trophies and sculptures. Other exhibits highlight du Pont’s passions for aviation, needlepoint, fox hunting, land preservation and the plight of abandoned animals.

When you leave the office and walk the grounds of Woodstock, you will still see older barns with the once familiar daffodil yellow and gray of Bohemia Stables. You can look out over spacious paddocks and imagine Kelso, Spray and Pete grazing and you can walk down trails enveloped by majestic trees and wonder if Allaire du Pont and her Kelly may have ever passed this way. The words on Kelso’s tombstone say: “Where he gallops the earth sings.”

It still does.

***

Hermitage Farm

Walk through the doors of the main office at Hermitage Farm in Goshen, Kentucky and, as you approach the front desk, you will see them. Framed memories. Snapshots in time. Reminders of a heritage which began to take root in the mid 1930’s and focuses on — the horse.

Lining an office wall are photographs of thoroughbred champions across nearly 70 years who have called this historic 700-acre estate home. Their accomplishments placed them, for a time, near the top of the horse racing world. They took home trophies for winning the Kentucky Derby, Kentucky Oaks, the Breeders’ Cup World Championships, the 2000 Guineas Stakes and, most recently, the Travers Stakes at Saratoga. Hermitage was home to the most expensive yearling ever sold at a public auction and also North America’s leading sire of 1980.

Located near Louisville and 80 miles west of Lexington, in the heart of Bluegrass Country, Hermitage Farm boasts a tradition on par with most of the large Kentucky farms. And to think it all began nearly two centuries ago…

The farm was purchased by Captain John Henshaw back in the early 1800’s and it remained in the family for nearly 100 years until it was sold in 1935. The buyer was a 19-year-old young man whose great-great-great uncle was the founder of the Kentucky Derby. And, soon, this young man would leave his own imprint on the history of thoroughbred racing.

His name was Warner L. Jones Jr. and he farmed the land, began with a single yearling and then added a mare. It was a simple beginning on a road that would see Hermitage become one of the most famous thoroughbred farms in America. Seventeen years later, Jones’ operation had increased significantly and one of his home-bred three-year-olds entered the starting gates as a 25-1 longshot in the 1953 Kentucky Derby. The colt’s name was Dark Star and he faced the daunting task of going up against the spectacular Native Dancer, who entered the Derby unbeaten in eleven races. Dark Star broke early, held a clear lead throughout and held off Native Dancer’s powerful finish to win by a head. It was one of the biggest upsets in Derby history and Hermitage Farm was suddenly on the map.

At the close of 1972, a stallion came to Hermitage who would take the farm to the highest level of thoroughbred breeding across the world. His name was Raja Baba. He was syndicated in 1972 in a 36-share deal at $10,000 per share. Ten years later, that selling price had increased to $205,000 per share on the open market and, later on in his career, a share reportedly sold for $380,000. As a freshman stallion in 1976, Raja Baba was the leading juvenile sire and, four years later, he became the overall leading sire in the United States.

Raja Baba died in 2002 at the age of 34. During his career at stud, he sired 62 stakes winners, two Breeders’ Cup winners and two champions. He brought attention to Hermitage over the years that opened other doors to success. In 1985, Warner Jones sold a half-brother to the Triple Crown champion Seattle Slew for a world record $13.1 million at Keeneland’s July Select Yearling Sale. The yearling’s name was Seattle Dancer. In that same year, Hermitage Farm set a record for the highest average price — $2,433,750 — for horses consigned for sale. It is a record that still stands.

In 1995, the Jones family sold Hermitage to 55-year-old Carl Pollard. It was Pollard’s vision to carry on the Hermitage tradition established before him.

Pollard and team began to buy mares and some yearling fillies to hopefully race and turn into broodmares. In 1999, Pollard purchased three fillies. One of the fillies was a small dark bay who was purchased for $180,000. Her name was Caressing. And, on a fall day in November of 2000, she reminded the racing world of Hermitage when, as the longest shot on the board at 47-1, she upset the field and won the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies world championship. Nearly three months later, Carl Pollard took his staff down to New Orleans as Caressing won the 2000 Eclipse Award for Champion 2-Year-Old Filly.

When Caressing retired and became a broodmare, she had some modest success but it was a mating in 2013 with Claiborne Farm’s Flatter, however, that changed everything. Caressing gave birth to a colt who was entered in the Keeneland September 2015 Yearling Sale. The colt sold for $425,000 and was named West Coast. In 2017, his victories included the Pennsylvania Derby (G1), the Travers Stakes (G1) and ran an impressive third in the Breeders’ Cup Classic (G1) in November (a race he is entered in this year as well). At year’s end, this son of an Eclipse Award winner captured his own when he received 3-Year-Old Male championship honors.

In 2003, Hermitage was purchased by Steve Wilson and Laura Lee Brown, owners of the Louisville-based 21C Museum Hotel chain. The married couple is fulfilling their long-term vision to create a destination celebrating the heritage of Kentucky and its signature industries — food, bourbon and horses. The historic main house, which has been the iconic image of Hermitage since 1835, has been restored and is available for rentals and events. Couples come here for their weddings and get the horses, rolling hills and a beautiful home. It encapsulates what they love so much about Kentucky.

During next May’s Kentucky Derby weekend, Hermitage will host tourists with the grand opening of a farm-to-table restaurant, a bourbon-tasting experience and a farmer’s market within one of the more than 30 barns on the property. And next to a creek at the back of the estate, visitors will eventually enjoy a studio projection-with-sound experience, where high-definition projectors display trees, hillsides, rocks and pools of water to create a totally immersive atmosphere. You might just see leaves in the trees turn into butterflies and fly away.

There is certainly excitement in the air with growing anticipation of expansion and tourist counts in coming years. But a new photograph has recently been added to the office wall in the main office during the past year. Multiple Grade 1-winner West Coast is symbolic of the farm’s heritage since Warner Jones bought his first yearling back in 1936. Broodmares, foals and yearlings continue to graze the land. In an industry that has seen its share of struggles in recent years, life goes on at Hermitage.

***

Iroquois Steeplechase

Mention Tennessee to most people and what normally comes to mind is country music. Music City, U.S.A. It is also a state known for its universities, the Great Smoky Mountains, Andrew Jackson and Elvis. While the state’s neighbor Kentucky to the north is known more for equine racing and breeding, there are more horses per capita in Shelby County, Tennessee than any other county in the United States.

And the state has its own annual rite of spring one week after the Kentucky Derby when the Iroquois Steeplechase is run on the second Saturday of May. On this one Saturday during the past 77 years, Percy Warner Park has been the heart of the steeplechase world and holds a deserving place in the history of American horse racing.

They begin arriving at Percy Warner Park before 8 a.m. on Saturday morning. The day’s seven-race card is still more than five hours away, but the competition almost feels secondary to the pageantry and the day-long party. Nearly 25,000 come from Tennessee and across the country each year to continue this annual celebration of horse, hats and hounds. They come wearing their fashionable Sunday best to attend the premier spring race meet in American steeplechasing. The Iroquois Steeplechase is more than just a horse race — it is a Nashville tradition that ties people from the community together.

A good portion of that community congregates in the park’s infield. Tailgating is an individually organized science here and thousands show up early to set up their tents. Even the infield has its strategic destinations and is divided into six regions known as Centerfield, Midfield, The Stretch, Topside, The Turn and The Meadows. Walk from tent to tent and you’ll encounter the finest in southern hospitality, live music, delightful cuisine and plenty of Tennessee Whiskey and Honey Jack Juleps, among various other libations.

The Iroquois Steeplechase has been run each year since 1941, with the exception of one year during World War II. The race has been run under threatening weather conditions and even endured the Nashville Flood of 2010. Remember, we are talking about a wide-open city park here. Tents can come in handy from time to time. And large VIP groups revel in tented luxury in the high-dollar Hunt Club, Paddock Club, Hospitality Village, Tents in the Turn and the Skybox Suites. Highly desired box seats overlook the grass track and have been passed down by families through the generations. Some families have retained their seats from the race’s earliest years in the 1940’s.

While many Iroquois attendees will tell you they come for the party, it is the thrill of steeplechase racing and the thoroughbreds that helps keeps fans at the park for the full day and coming back year after year. In the steeplechase world, these Nashville races have the largest purses of the spring season. The day is comprised of seven races for horses aged 4 years and up over the three-mile turf track for more than $500,000 in purses, bonuses and awards. The Iroquois Steeplechase is run by a nonprofit organization and, since 1981, has raised more than $10 million for the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at nearby Vanderbilt University.

The Iroquois course is regarded as one of the best racing surfaces in the country and was one of the first steeplechase courses to use an irrigation system, which is maintained year-round. The races on the course range in distance from 2 ¼ to 3 miles over a series of four-foot national and timber fences. The race day builds and culminates with the running of the $200,000 Grade 1 Calvin Houghland Iroquois Hurdle Stakes. The winners of the Iroquois over the years have included a Who’s Who of some of the greatest of American steeplechase horses, including Eclipse Award champions Flatterer, Lonesome Glory, Correggio, All Gong, Good Night Shirt, Divine Fortune, Rawnaq and 2017 champion Scorpiancer.

To commemorate 75 years in 2016, the Iroquois Steeplechase created what is known as the TVV-Iroquois Cheltenham Challenge — a transatlantic rivalry that includes two of the world’s biggest steeplechase races, the Iroquois Steeplechase in Nashville, and the Cheltenham Festival in England. The partnership offers a $500,000 bonus challenge to any horse that can win both the Ryannair Group 1 World Hurdle at Cheltenham in March and the Calvin Houghland Iroquois in May, or vice versa, within a 12-month period.

Year after year, the Iroquois Steeplechase can best be described as a celebration — of spring, of pageantry and of horse racing at its finest.

***

Secretariat’s Foaling Shed

Exterior of Secretariat’s foaling shed (photo by Tom Ferry).

It happened here shortly after midnight on March 30, 1970. Outside, it was a cold and rainy early Virginia morning; yet, inside the small wood-frame foaling shed, Meadow Farm manager Howard Gentry, his assistant Raymond Wood and night watchman Bob Southworth, were focused on an 18-year-old mare named Somethingroyal. She was giving birth and Gentry helped ease her foal’s folded foreleg out of the birth canal.

After the newborn male’s hips popped out, Gentry exclaimed, “There’s a whopper.”

The farm vet arrived shortly afterwards and said years later, “He was beautiful. He was well put together, correct; his legs were perfect. He had a beautiful head and was as red as fire.”

The morning sun would soon rise and the world of horse racing had changed forever.

The real-life birth of Secretariat bore little resemblance to the one portrayed in the 2010 Disney movie. Owner Penny Chenery, trainer Lucien Laurin and groom Eddie Sweat were not there — but the modest little structure made of whitewashed barn board was and is present today. Located in the Meadow Event Park in Caroline County, Virginia, Secretariat’s foaling shed was named to the National Register of Historic Places by the National Park Service in 2015. It is a part of land that dates back to 1805.

Some of the original blue paint is still visible on Secretariat’s foaling shed (photo by Tom Ferry).

In 1936, Christopher T. Chenery purchased The Meadow, an ancestral property near Doswell, Virginia and not far from his boyhood home in Ashland, Virginia. Soon afterwards, Chenery created Meadow Stud, which bred thoroughbreds and raced them in the now iconic silks highlighted by blue and white blocks. Over the years, Chenery and Meadow Stable produced numerous champions including Hall of Famers Hill Prince and Cicada.

In 1965, Chenery partnered with Ogden Phipps in a foal-sharing agreement. Phipps owned leading sire Bold Ruler and sought out Chenery’s best mares at Meadow Stable. After Chenery fell ill and was hospitalized in 1968, Phipps and Chenery’s daughter Penny flipped a coin the following year to determine who would win first choice of Bold Ruler’s foals out of Somethingroyal. Phipps won the toss and selected the first foal, a filly named The Bride. The filly ultimately ran four times and never won a dollar. Penny Chenery had to “settle” for the second foal, a male — and the rest of the story is legendary.

The Chenery family sold the Meadow Farm land in 1978 and, in 2003, it was purchased by the State Fair of Virginia, which turned it into the Meadow Event Park. The 331-acre property is currently owned by the Virginia Farm Bureau Federation. Within the Event Park is the “Meadow Historic District”. This includes Secretariat’s training barn where he wore his first saddle and bridle, the yearling barn where he and the great Riva Ridge lived as colts, and a stallion barn, pump house, well house and horse cemetery. As the years rolled by, the original broodmare barn could not be restored; however, visitors can still gaze upon the “Cove,” the expansive grassy field in a valley where the Meadow mares and foals once grazed.

What most tourists from across the country and around the world come to see, however, is the foaling shed. There are few places its equal when it comes to sacred ground in the world of horse racing. When approaching the shed’s entrance, one instantly sees the remaining fragments of Meadow Stable blue paint which still cling to the lower half of the inside portion of the door. And upon entering the shed, you find yourself in a small partitioned area. It is here that Secretariat came into the world. There is very little to see, but much to imagine.

Throughout the year, the Meadow Event Park provides “Hoofprints of History” tours of the Historic District. Visitors can stop by the legendary barns and grounds, as well as view pictorial galleries and rare exhibits that illustrate Meadow Stable’s glory days. And they can marvel at how such humble surroundings could host what is arguably the greatest of all American thoroughbreds.

***

Home of Seabiscuit

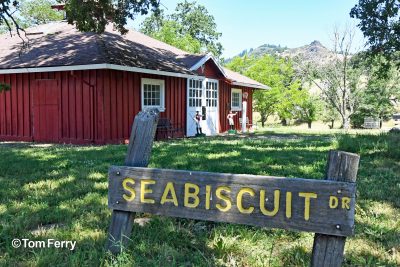

Seabiscuit’s stud barn is listed in the National Register of Historic Places (photo by Tom Ferry).

If you told somebody the story before they read the book or saw the movie, they wouldn’t believe you.

They would be skeptical that a beaten-down horse that won less than a quarter of its first 40 races could have inspired millions during the Great Depression. And if you told them both horse and jockey each suffered what were thought to be career-ending leg injuries, yet would recuperate together and come back to win one of the richest races in history, they might have laughed out loud.

Yet it happened. And the faces and places were real.

While it has been more than 70 years since he walked the earth, there is no site where the spirit of Seabiscuit is more alive than at his longtime home of Ridgewood Ranch in Willits, California. Located 2 ½ hours north of San Francisco on 5,000 acres of Northern California oak and redwood-studded hillsides, Charles S. Howard purchased this land as a cattle ranch and second home in 1919. One decade later, he had transformed a portion of the ranch into a Thoroughbred breeding and training operation. This included a 90-acre central area, highlighted by several historic structures still present at Ridgewood.

One, however, is more iconic than all the others — Seabiscuit’s stud barn. This wood-framed building, clad with red board and batten siding and white, flat-sawn window and door trim, holds a special place in the annals of horse racing. It was here where Seabiscuit rehabilitated for the better part of 1939. It was here where he retired the year after his thrilling comeback race in the Santa Anita Handicap and began a stud career that saw him sire 108 foals.

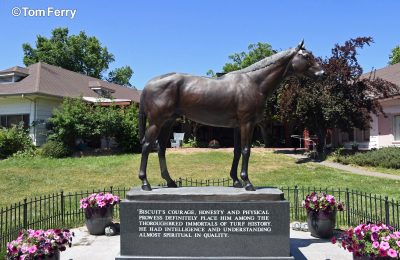

Seabiscuit’s statue sits in front of the one-time home to the Howards (photo by Tom Ferry).

Visible in so many photographs, the barn was a destination for more than 50,000 visitors from 1940 until 1947. During the initial seven months of 1941, an incredible 33,072 people signed the guestbook outside his stall. Charles Howard posted a welcome sign at the entrance to the farm and built a small grandstand for visitors just outside the horse’s stall.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, Howard designed the barn specifically for Seabiscuit. The four stalls inside the barn, one in each corner, were originally accessed by four large paddocks, however, only the stalls remain today. Those stall doors are adorned with the names of great horses owned by the Howard family through the years including Noor, Kayak II, Ajax and, of course, The Biscuit. The Howard family sold the whole estate in the early 1960s and the stud barn was restored in 2004 after many years of serving as a storage facility and printing office. There are several artifacts from the Howard era that are still present in the barn and these include the horse-and-rider weather vane on the roof and two red-and-white lawn jockey figurines.

Within view of the stud barn is the lavish, Craftsman style, one-time home to Charles and Marcela Howard. The home’s interior appears frozen in time, as if the Howards could walk in at any moment. In front of the home stands a beautiful bronze statue of Seabiscuit. It is a replica of the Ridgewood original which was moved to the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, NY.

Charles and Marcela had several Hollywood celebrity friends who were frequent visitors to Ridgewood, including Bing Crosby, Clark Gable and Carole Lombard. Walk the grounds of the ranch and you’ll pass the pool where child star Shirley Temple learned to swim. The restored carriage house was home to automobiles during the glory years and one can also see the bath houses once used by family and guests. There are the historic mare barns whose barn doors are still adorned with the iconic red, white triangle and “H” logo present on Howard racing silks.

Seabiscuit’s stall (photo by Tom Ferry).

Drive throughout the Ridgewood area and you might get lucky and see white or fallow deer which Charles Howard introduced to the area in 1949 when he purchased 53 of the deer from his friend William Randolph Hearst. The land is also home to several native species including the golden eagle and California mountain lion. When driving around the ranch, it is also sobering to know it is here where Howard’s 15-year-old son Frank was killed in a vehicle accident in May of 1926. The tragedy led Howard to fund the construction of the Frank R. Howard Memorial Hospital which opened two years later in Willits.

In 1962, Christ’s Church of the Golden Rule purchased the ranch and owns it to this day. It has taken steps to preserve the ranch’s historic and environmental value and the restoration of historic buildings is ongoing. The ranch began giving historic tours in 2001, shortly after Laura Hillebrand’s award-winning Seabiscuit: An American Legend was published, and they are still available from June-September.

There is one thing visitors will not see — Seabiscuit’s final resting place. On May 17, 1947, he died six days short of his 14th birthday. A heart-broken Charles Howard buried the horse at an undisclosed location on the grounds, somewhere under a newly-planted oak tree. The location of that tree remains a Howard family secret to this day. It doesn’t really matter, however, because visitors to Ridgewood Ranch will sense his presence everywhere.

***

Against All Odds Statue

What is most compelling is not the statue, but, rather, what it represents — the fighting spirit of community and the warrior hearts of two racehorses. It is a place where one can stop and remember, or simply imagine.

John Henry’s trainer Ronald McAnally in front of the Against All Odds statue at Arlington Park (photo by Tom Ferry).

Five-time Kentucky Derby-winning trainer D. Wayne Lukas once said if someone has never been to a racetrack before, their maiden voyage should be to Arlington International Racecourse. Each year, from the first Friday in May until the leaves begin to show traces of burnt orange in late September, this majestic racetrack, located 30 miles northwest of Chicago, plays host to trainers, jockeys and horses from across the Midwest and throughout the racing world. It is a track with a grand history and if one were asked to describe Arlington’s past and present with one word, the answer would be perseverance.

The bronze statue is hard to miss by anyone entering the racecourse, as it sits on a balcony overlooking a beautiful paddock. Named Against All Odds, the sculpture was designed by internationally renowned equine artist Edwin Bogucki, who also created the bronze Secretariat statue at the Kentucky Horse Park. Unveiled in 1989, Against All Odds captures one of the great moments in thoroughbred horse racing history. Eight years earlier, Arlington Park introduced the first $1,000,000 thoroughbred race. The race has had different names over 27 years, but today it is known simply as the Arlington Million. It is run each August and gathers some of the world’s great turf stars during the annual International Festival of Racing.

The inaugural race on August 30, 1981 was broadcast on NBC to an estimated TV audience of more than 50 million. The richest race in history needed a great horse and it got one in the incomparable 6-year-old gelding John Henry, while also introducing us to a little-known Irish 5-year-old named The Bart.

John Henry struggled early on in the race with a rain-soaked turf, falling back to eighth. At the half mile call, however, he found his footing and began to move up along the rail with a rhythmic stride, as Key to Content and 40-1 longshot The Bart battled for the lead. As the field of 12 hit the top of the stretch, the crowd of 30,637 roared as John Henry made his move.

He and jockey Bill Shoemaker exploded down the middle of the track in full pursuit of The Bart, who had disposed of Key to the Content. John Henry closed the gap with each stride and finally caught his opponent at the wire — but the end result was too close to call.

To most, it appeared The Bart had won by a narrow margin. The photo finish sign remained up for six minutes and when, at last, the board flashed the official results, the never-say-die John Henry had done it again in seemingly impossible fashion. With incredibly meticulous detail, the statue captures this final moment with jockey Eddie Delahoussaye aboard The Bart and Shoemaker on John Henry. The life-like monument includes names on the saddle cloths and captures the look of determination, heart and soul in the eyes of both horses and jockeys alike. Upon completion of the maiden Arlington Million, the future of the new and exciting turf race looked extremely bright. But everything changed four years later in the very early morning hours of July 31, 1985.

Richard L. Duchossois (photo by Tom Ferry).

Richard L. Duchossois received the phone call sometime after midnight telling him his racetrack was on fire. Arlington’s majority owner stood in Arlington’s parking lot around 4 a.m. and watched helplessly as the biggest fire the Chicago’s modern suburbs had ever seen to that point blazed out of control. Ultimately, more than 4,000 gallons of water per minute were used to combat the fire — but it just wasn’t enough. Duchossois later said he wasn’t concerned about saving the facility because it was beyond saving.

The fifth running of the Arlington Million was 25 days away.

In World War II, Duchossois commanded a tank battalion and on Sept. 15, 1944, he was shot in the side as his battalion crossed the Moselle River. The bullet caused nerve damage to his back and he was temporarily paralyzed from the neck down. His body was placed in a grouping of soldiers marked for dead, yet he was rescued and recovered. Four months later, he was hit in the face with a fragment of a grenade, yet rebounded once more. He received the Purple Heart for his injuries and his war experience taught him the power of teamwork, camaraderie and… resilience.

The day after the fire, Duchossois, Sheldon Robbins and the other owners mobilized and came up with a plan to remove the smoldering rubble and prepare the track for the Arlington Million. On Aug. 5, 1985, more than 200 crews worked practically around the clock, 20 hours a day, removing 7,000 tons of steel and 14,000 tons of other debris left behind by the fire. A 271,000 square foot area of new blacktop was created and, on it, was erected 43 red-and-white tents and temporary bleachers. Those who believed refused to say die and, on Aug. 25, “The Miracle Million” was run in front of a crowd of 35,651. Work began immediately afterwards on rebuilding the track. Four years later, in 1989, the work was completed and one of the most spectacular racing venues in the world was unveiled.

Arlington Park was rebuilt post-fire into one of the world’s most spectacular tracks (photo by Tom Ferry).

The Against All Odds statue is symbolic of the track’s 91 years. Perhaps a plaque alongside the statue says it best: “During its entire history, Arlington International Racecourse displayed the desire, the courage and the ability to transform adversity into success.”

***

Dan Patch Barn

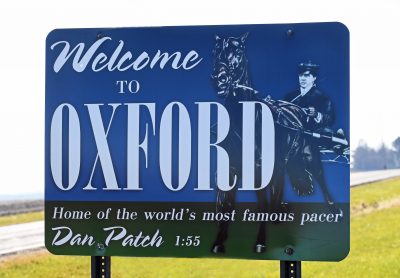

Sign in Oxford, Indiana (photo by Tom Ferry).

Walk around this small Indiana town of fewer than 1,200 residents and he is everywhere. He has a small cafe named after him and you will find him on the top of the town’s water tower. His likeness welcomes you on billboards as you enter the city limits and you will find him on varied murals, plaques and street signs throughout the town.

And yet, he left town for good nearly 116 years ago.

Each decade across those many years has showcased legendary athletes who captivated America and often transcended sports by branching into popular culture.

Their names are familiar to the average American sports fan in spite of passing time: Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Red Grange, Bobby Jones, Jesse Owens, Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan.

But more than a century ago, from 1900-1909, a superstar in the world of sports captured the hearts and minds of Americans unlike any before him. He was a household name who endorsed cigars, washing machines, automobiles, toys, watches and much more. More than 90,000 people from all walks of life would routinely come from miles away and gather at local fairgrounds to see him compete. Today, however, his name and exploits are largely forgotten.

His name was Dan Patch and he was called the “Epitome of Excellence in American Sports.” And even though he was billed as “kindhearted, generous and a staunch Methodist who never performed on a Sunday,” this idol was not human. He was, though, arguably the greatest harness racing horse who ever lived.

Dan grew up in the small town of Oxford, Indiana in a barn that still stands today. The horse’s owner, Daniel Messner Jr., was a local storekeeper in Oxford who had aspirations of grandeur when he bred his five-year-old mare Zelica to the champion standardbred stallion Joe Patchen. Those dreams were quickly shattered on April 29, 1896 when the newborn foal arrived with legs so crooked and knees so knobby that some thought it would be a blessing if he didn’t survive the night.

But survive he did. In the winter of 1899, three-year-old Dan Patch would often be seen pulling a cart through Oxford’s snowy streets, trailed by young boys who grabbed on the back and were pulled on their sleds for a free ride. Residents of the small town always thought of Dan as their own.

At Dan Patch’s racing debut at a nearby fair during the late summer of 1900, it was reported every store in Oxford shut their doors so residents could journey to see him race. During the next two years, Dan’s fame grew as he raced at tracks throughout the midwest and on the East Coast at summer fairs and exhibitions. At the conclusion of each summer’s Grand Circuit, he would return to Oxford and the adulation of hundreds who would cheer his arrival at the train station. He would lead the walking procession back to his barn and those who were there stated he knew exactly how to navigate his way back to his stall.

Dan Messner would routinely turn down offers to sell the horse, but, in early 1902, an offer of $20,000 was too tempting and Dan Patch was sold. On March 18, 1902, the beloved hometown champion left Oxford by train and journeyed on to immortality. Dan would race across America during the next seven years and be viewed and loved by thousands. He never lost a race and set a world record in the mile that would stand for 32 years.

The Dan Patch Café (photo by Tom Ferry).

Like so many small towns across America, Oxford has suffered during the past half-century from the completion of the interstate highway system. People no longer needed to travel secondary roads that took them through the business districts of small towns in order to get to their ultimate destination. And unlike previous generations, baby boomers have often moved on from the towns of their birth to brighter lights, different lifestyles and better jobs. Passing time in Oxford has seen the closure of the high school, bowling alley, movie theater, speakeasy and even Dan Messner’s general store. One thing remains, however, and that is local pride in Dan Patch.

Each September, the hometown horse is remembered during the town’s annual Dan Patch Days festival. His original 60×44 foot barn continues to sit nearly 75 feet from the Messner home. Dan Messner boarded up the structure before he bought his first automobile in 1914. The Messner family continues to reside in the home to this day, yet have never entered the barn’s interior that remained boarded up for nearly 100 years. The family did, however, keep up the exterior. Messner’s son Richard lived in Oxford until his death in 1992 and repainted the barn’s roof every few years with the phrase that is still present today, “Home of Dan Patch 1:55.”

The barn was finally opened in February 2006 when Dan Messner’s grandson and the home’s current resident John Messner and his wife Pam began a major renovation to the structure. Discovered in its interior were, among other things, remnants of two sulkies, three horse stalls and Dan Patch’s tack trunk, bearing the horse’s name in faded letters. And on the slats within what once was Dan’s stall, you could look closely and see evidence of cribbing marks. While the barn is only open to the public on special occasions, this permanent landmark draws a steady number of passersbys throughout the year who will stop their cars and take photos… and try to imagine a time, a place, a man and a horse.

***

The Twin Spires

Horse galloping past the Twin Spires of Churchill Downs (photo by Tom Ferry).

If Churchill Downs is American thoroughbred horse racing’s cathedral, then its steeple and eternal landmark is the Twin Spires. These two pinnacles cast a glow up and down Louisville, Kentucky’s Central Avenue and across the landscape of horse racing history.

The Spires are easily the most recognizable symbol in the Sport of Kings and, arguably, in all of sports. It is difficult to take a mental portrait of the Churchill Downs racecourse where the spires are not present and prominent.

In the late spring of 1894, the first 20 editions of the Kentucky Derby had come and gone and the Churchill Downs track (then called the Louisville Jockey Club) was facing bankruptcy. Twenty-four-year-old architect Joseph Dominic Baldez was contacted to help build the track’s new grandstand.

Original plans did not call for the spires and they were pretty much an afterthought. Baldez felt the grandstand required something to accentuate its appearance and give it pizzazz. The spire was a very popular architectural element during the late 1800s and Baldez had a style based on symmetry and balance. As a result, the spires are 12 feet wide, 134 feet from center to center and rise 55 feet from the grandstand’s roofline to the top of the adorning king posts. Each spire has eight rounded, closed windows that were originally left open in their early days.

The Twin Spires made their debut on Monday, May 6, 1895 at the 21st Kentucky Derby. Thus, the Run for the Roses hasn’t always been held on the first Saturday in May — but close enough.

The Spires have grown in mystique with passing time and even adorned Kentucky license plates for close to ten years. Yet, the sun shines bright on the entirety of Churchill Downs. Take a walk through the grounds and you will find an engaging mix of the old and the new. Every Derby champion is listed on plaques throughout the concourse. The very first champion, Aristides, has been memorialized with a statue in the paddock, as has Hall of Fame jockey Pat Day.

The Twin Spires (photo by Tom Ferry).

In recent years, additions have included new luxury suites, a Turf Club and lounge, a Skye Terrace, new Millionaire’s Row, increased restroom facilities and new balconies, overlooking both the track and the paddock. Perhaps most stunning was the addition of two massive towers to the left and right of the Twin Spires. The towers brought 2,800 additional seats to the total capacity but have not detracted all that much from the majesty of the spires.

Walk the corridors beneath the grandstand and you will come across the old, abandoned betting windows. An eyesore? Not really, but rather nostalgic, lasting memories of days gone by. And when you leave the paddock and stroll through the tunnel heading out to the track, stop and pause for a minute and imagine the great horses and humans that once tread this ground.

One day a year, the eyes of the sports world are focused on Churchill Downs. The track is filled with decorative spring hats, mint juleps, celebrities, pageantry and, of course, roses. The Twin Spires, however, stand tall during winter, spring, summer and fall.

The total cost of the 1894-95 grandstand construction and the Twin Spires was all of $42,000. Former Churchill Downs president Matt Winn reportedly told spires architect Baldez, “Joe, when you die, there’s one monument that will never be taken down — the Twin Spires.”

More than 120 years have passed and Churchill Downs has seen a pretty good return on that initial investment.

***

The White Pine

The White Pine (photo by Tom Ferry).

Of all the great landmarks in American horse racing, perhaps only one is truly alive — and it resides at Belmont Park in Elmont, New York.

It has been there to witness 13 horses achieve the greatest moment of their lives when they captured the sport’s most elusive honor, the U.S. Thoroughbred Triple Crown. And it watched from afar as Go For Wand, Prairie Bayou, Timely Writer and the great Ruffian left the paddock to head out to the track — only to never return.

It has seen its share of both horses and people across many, many years. Some say more than three centuries, but the New York Racing Association approximates the age at between 175-190 years old.

It is a tree.

Not just any tree, however, but a huge Japanese white pine, specifically known as Pinus Parviflora. The shade it casts across the Belmont Park paddock predates the track itself, which was constructed in 1903.

Before there was Belmont Park, the land the tree resides on was part of the Manice estate. A 19th century Tudor-Gothic mansion stood on the estate and, until it was torn down in 1956, it served as the headquarters of Belmont’s Turf and Field Club. It was said that the mansion “stood in a setting of ancient trees” (from New York Racing Association’s Belmont Park: 1905-1968).

Trees surely dominated the Manice property. And it’s no small feat the White Pine has survived so long, considering a sawmill reportedly stood on the Belmont land to “handle the vast amount of lumber needed for construction of the stands, barns and other buildings.”